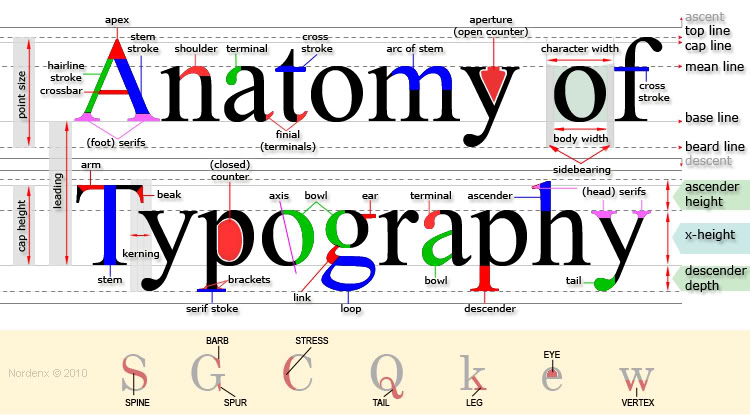

These had more constructed letterforms, catching up to the steely calligraphy of the period, and daringly slender horizontals and serif details that could show off the increasingly high quality of paper and printing technology of the period.

These typefaces had a far greater amount of stroke contrast than before, with the difference in stroke width much greater than in earlier types.

Starting in the seventeenth century, typefounders developed what are now called transitional and then "modern" or Didone types. The serifs have been thickened and the contrast is minimal. Ī conventional slab-serif typeface, Rockwell. )įrom the arrival of roman type around 1475 to the late eighteenth century, relatively little development in letter design took place, as most fonts of the period were intended for body text, and they stayed relatively similar in design and rooted in traditions of Italian humanistic handwriting. (The Hebrew alphabet, in contrast, is normally "reverse-contrast" from a Latin-alphabet perspective, as the verticals are lighter. Early 'roman' or ' antiqua' type followed this model, often placing the thinnest point of letters at an angle and downstrokes heavier than upstrokes, mimicking the writing of a right-handed writer holding a quill pen. Throughout the development of the modern Latin alphabet with an upper-case based on Roman square capitals and lower-case based on handwriting, it has been the norm for the vertical lines to generally be slightly thicker than the horizontals.

The narrowest part of the stroke is at top left/bottom right, so the axis is diagonal. Historical background ĭiagonal angle of stress in the typeface Centaur, based on 1470s Venetian printing. There is no connection to reverse-contrast printing, where light text is printed on a black background. The reverse-contrast effect has been extended to other kinds of typeface, such as sans-serifs. They could be considered as slab serif designs because of the thickened serifs, and are often characterised as part of that genre. They were particularly common in the nineteenth century, and have been revived occasionally since then. Reverse-contrast letters are rarely used for body text, being more used in display applications such as headings and posters, in which the unusual structure may be particularly eye-catching. Modern font designer Peter Biľak, who has created a design in the genre, has described them as "a dirty trick to create freakish letterforms that stood out." The style invented in the early nineteenth century as attention-grabbing novelty display designs. The result is a dramatic effect, in which the letters seem to have been printed the wrong way round.

This is the reverse of the vertical lines being the same width or thicker than horizontals, which is normal in Latin-alphabet writing and especially printing. Ī reverse-contrast or reverse-stress letterform is a design in which the stress is reversed from the norm: a typeface or custom lettering where the horizontal lines are the thickest. Both typefaces are very bold, but the fat face's thick lines are the verticals as normal and the Italian's are the horizontals. Shown below it is a " fat face" design, a type also popular in early 19th century printing. Reverse-contrast "Italian" type in an 1828 specimen book by the George Bruce company of New York.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)